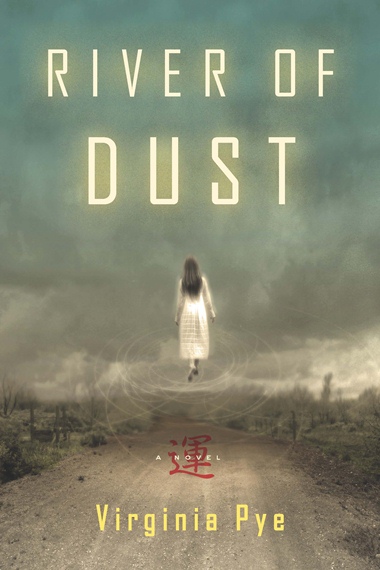

Virginia Pye’s novel, River

of Dust, opens in 1910, less than

a decade after the Boxer Rebellion when Christian missionaries were massacred

and foreigners were either killed or driven out of the country. Reverend John

Wesley Watson and his wife Grace have lived on northwestern China’s windswept

plains for four years. Their toddler son

Wesley was born in their missionary village and Grace is pregnant again after

miscarrying. They’ve just arrived with

servants Mai Lin and Acho at a remote “vacation home” outside the missionary

compound when two Mongolian nomads charge across their land. One of the men

yells “Death to Lord Jesus!” Grace begs the men to leave them alone and

offers them the family’s cow telling them “Let

us be. Certainly, we have done nothing

to harm you.” Her words infuriate

the men and the younger man snatches Rev. Watson’s handkerchief from his pocket

and stuffs it into one of his many pouches where Grace notices another “strip

of cloth that appeared to be of the same fine linen as her husband’s

handkerchief.” Her husband tells her to

take her son inside and lock the doors but as she flees the man sweeps down and

grabs her son’s arm. She holds on until “the barbarian stopped toying with

Grace and simply yanked her son away.

She would never forget how easily Wesley was lost to her, as if to show that

. . . They could take whatever they pleased.

And what they wanted was not her but the child.”

Rev. Watson and Acho immediately set off to recapture Wesley.

“The Reverend bore nothing except his fury, height, and stature as a Man of God

in a land of infidels. That would have

to be enough.” Their search leads them

to a remote opium den where Rev. Watson is shot but saved by the book of poems

in his breast pocket. To the Chinese who call him Ghost Man, this validates the

legends surrounding him even after another shot injures him.

In the following weeks as Rev. Watson recuperates, search

parties comb the Shansi Desert looking for Wesley and the Watsons continue to

believe that Wesley will be found. Once

Rev. Watson regains his health, he and Acho spend months searching for Wesley,

returning to the compound only occasionally. Rev. Watson seems to others in the

compound to be disturbed and the amulets, talismans, and massive fur he wears

make the other missionary families uneasy.

Grace, however, never gives up hope. “There was no denying she was a cheerful Midwestern girl at heart: an

American girl, synonymous with optimism.

And in so being, she understood that she must endure her greatest

punishment. She must live with the hope,

the infernal hope that love could survive even out here where nothing else did.

Her son would return to her. She just

knew it.”

Grace tells her husband, “It

isn’t your fault. . . Please don’t blame yourself.”

“But it is, and I do,”

says Rev. Watson.

This novel of retribution contains clues like Rev. Watson’s

handkerchief that warn the reader that there’s a backstory behind the nomads’ actions.

That backstory and the way in which the land serves as a character form

something of an Old Testament-like rendering. During the Reverend’s absence,

the area has fallen into a deep drought and dust covers every surface. Children

are dying, no one has any hope, and Grace increasingly turns to Mai Lin’s

potions to maintain “the correct balance” in her life. She sees visions and

tries to find blessings in her surroundings but her faith begins to waver.

I don’t know if River

of Dust was intended as a tribute to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in its exploration of savagery versus civilization

and in the Reverend’s god-like appearance to the Chinese but comparing the two

is inevitable. Rev. Watson’s wearing of

“non-Christian” garb and his odd associations coupled with Grace’s reliance on

her amah, Mai Lin, show the not-so-subtle changes in the couple’s beliefs. The

novel’s vivid imagery of the physical changes in both Rev. Watson and his wife makes

the reader feel each character’s journey better than any simple telling of it

might do.

Pyes’ novel is informed by the life of her grandfather, the

Reverend Watts O. Pye, one of the first missionaries to return to Shanxi

Province less than a decade after the 1900 Boxer Rebellion. Her grandmother, Gertrude Chaney, had three

children in Shanxi. Her two daughters

died young and her son Lucien Pye was the only one to live to adulthood. Watts Pye died when Lucien was five and he

and Gertrude Chaney remained in China even under the Japanese occupation. Lucien

Pye went to college in the U.S., served as a translator for the U.S. Marines

during World War II then studied at Yale under the G.I. Bill. He wrote over

twenty books on China and Asia. Watts

Pye’s diaries along with stories Virginia Pye heard while having tea parties

with her grandmother using her fine Chinese porcelain infuse this novel with a

unique voice, perspective, and authenticity.

Summing it Up: Read River

of Dust for a view of 1910 China that will inform, entertain, and enlighten

you. Savor it for Pye’s ability to show

the changes in her characters through their actions and for the way she makes

Acho and Mai Lin delightfully real and complex.

Choose it for your book club to discuss the influence of the culture of

the time and the nature of circumstances that can alter beliefs and faith. Note: Ms. Pye is happy to meet with book

groups (http://virginiapye.com/bookclubs.html).

Rating: 4 stars

Category: Historical Fiction, Gourmet, Super Nutrition, Book

Club

Publication date: May 14, 2013

Author’s Website: http://virginiapye.com/index.html

Book Trailer: https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B9meL215HlDJb1lrcWZDTThadlU/edit

Book Trailer: https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B9meL215HlDJb1lrcWZDTThadlU/edit

Reading Group Guide: http://unbridledbooks.com/images/uploads/pdfs/RiverDust_RG.pdf

Publisher’s Website and Excerpt: http://unbridledbooks.com/our_books/book/river_of_dust

What Others are Saying:

"Terrific, tremendous, wonderful...a strong, beautiful, deep

book." –Annie Dillard

on River of Dust by Virginia Pye

on River of Dust by Virginia Pye

“A

vividly imagined and beautifully drawn picture of the life of Christian

missionaries in China in the early 20th century.”—- Jung Chang, author of Wild

Swans: Three Daughters of China; co-author, Mao:

the Unknown Story

“Virginia

Pye’s River of Dust is a remarkable novel in the ways that delight me the most:

It has a compelling narrative voice, a dynamic story and a deep resonance into

the universal human condition, all of which is inextricably bound together.

This is a major work by a splendid writer.”

–Robert Olen Butler'

No comments:

Post a Comment